Survey data collection from start to finish

Surveys have long been a staple of social science research on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors. In recent years, however, we have witnessed a strong shift from secondary analyses of large general social surveys toward smaller, more targeted primary data collections. This development has been accompanied by the increasing availability of affordable and easy-to-implement surveys using online access panels. While the entry barriers to original survey-based research are now likely lower than ever before, it still comes with notable methodological, administrative, and logistic challenges. To help aspiring survey researchers navigate this process, this Methods Bites Instructional by Joshua Hellyer (MZES, University of Mannheim) provides a comprehensive guide to survey data collection with online access panels.

Reading this blog post, you will learn:

- The steps involved in planning and conducting a survey experiment

- Best practices in reproducibility

- Tips on completing your application for ethical approval

- Pros and cons of working with an online access panel

Note: This blog post provides a summary of Joshua’s and Johanna Gereke’s input talk “Survey data collection from start to finish: Designing & executing reproducible research with an online access panel” in the MZES Social Science Data Lab in Spring 2022. The original workshop materials, including slides and scripts, are available from our GitHub. A live recording of the talk is available on our YouTube Channel.

Overview

Introduction

In this blog post, I will walk you through the process of fielding your own survey experiment using an online access panel. Online access panels are pre-selected groups of internet users who are paid to participate in various surveys, often including market research as well as scientific studies. You may have heard of panel providers like Bilendi/Respondi, Dynata, Kantar, and YouGov that are frequently used in social science research. They have become popular among social scientists because they are a relatively fast, easy, and cheap way to reach a sample of the general population, but there are certainly pros and cons that you should consider, as I will describe in this post.

Throughout this post, I will use a recent data collection as an example, a survey experiment that I conducted with Johanna Gereke (whose expertise I rely on extensively for this piece) and several other colleagues about demographic threat and how it affects group boundaries in the German context (Gereke et al. 2022). In some ways, this project is unique: it was completed as part of a replication seminar at the University of Mannheim, in which we worked with 12 Master’s and PhD students who helped plan the survey, analyze data, and write the first draft of our paper. But in many other ways, our experiences should apply to a wide range of potential surveys, and I hope that you will find it useful no matter the size of your research team or the topic you plan to study.

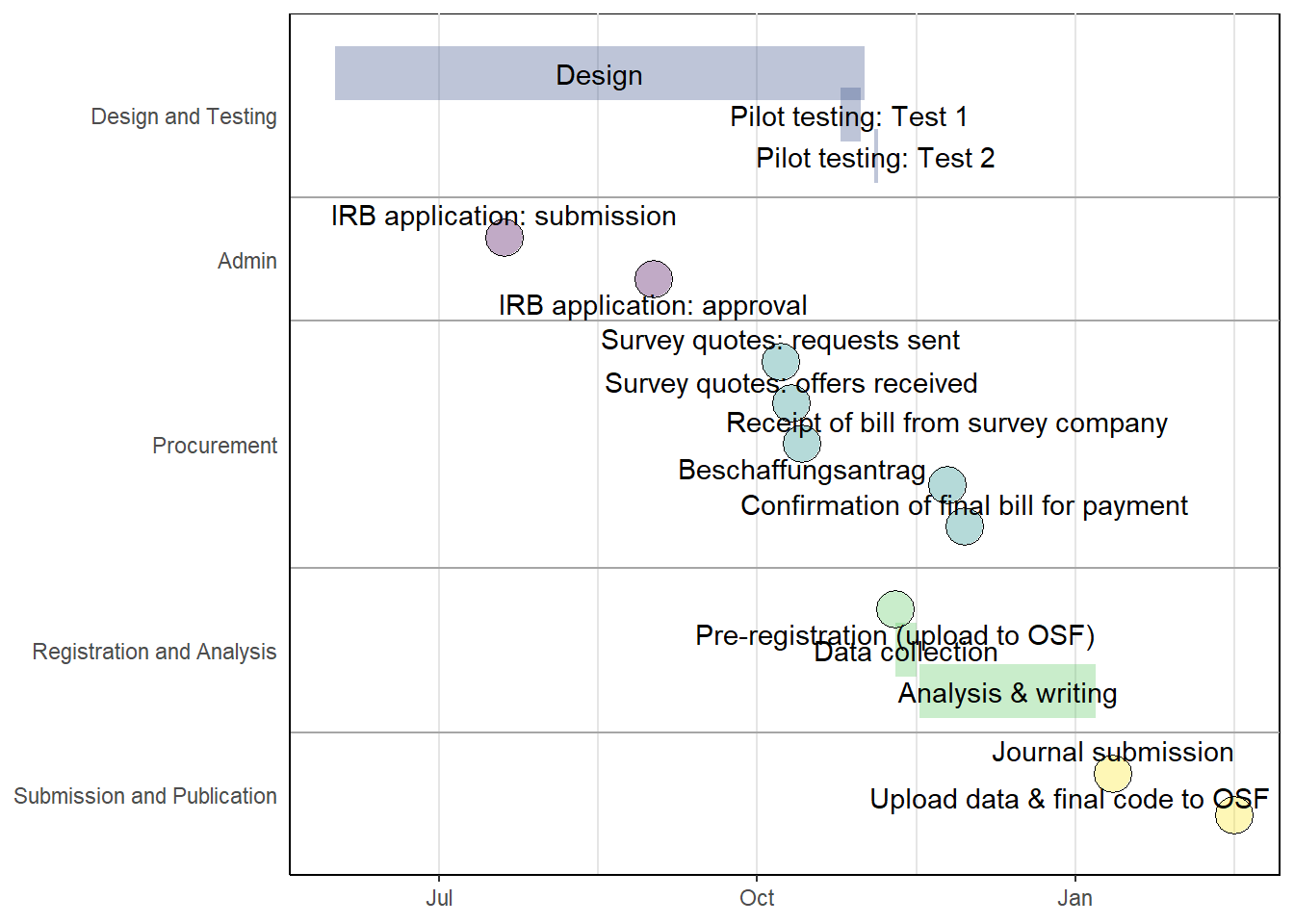

So, what steps are required to plan and execute a survey experiment? Your experience may vary depending on the complexity of your planned survey as well as the population you plan to sample from, but you can get an overview of our recent experience in the timeline shown in the figure below. This project was completed relatively quickly, going from initial conception to journal submission in just over 6 months. This timeline was intentionally fast, as we wanted the students to experience the whole data collection process in a single semester, but this is also an example of just how fast you can collect data using an online access panel. As you can see, the most time-consuming part of our research was designing the survey, but also note that ethical approval can take some time (more on this later). While your workflow may look a bit different, I would generally recommend proceeding in a similar order. In particular, ethical approval must come early in the process as you need this to collect any data. Tackling elements like this (and also procurement) that are out of your control early on can save you from delays later.

Figure 1: Project timeline.

Research Design

For our seminar, we chose to first replicate and then extend Maria Abascal’s recent work on group boundaries in the U.S. context (Abascal 2020). She finds that when white Americans are confronted with information about demographic threat, i.e. that they will no longer make up a majority of the U.S. population, they are more exclusive about who they see as “White”. We tested whether the same effect could be found in Germany, randomly assigning each of our participants to see one of two demographic projections that either predicted that people with a migration background would make up an equal share of the population in the future (treatment), or that they would remain a minority (control). After seeing this, participants rated pictures of 18 people as having a migration background or not. We hypothesized that following Abascal, the demographic threat treatment would make people more likely to classify people who appear ethnically ambiguous as having a migration background.

Questionnaire

Because our experiment was based on previous research, designing our survey was perhaps more straightforward than it otherwise would have been. However, adapting the questionnaire to the German context still required a lot of consideration.

When writing your questionnaire, it is always good to start by looking in the literature for examples of how other people have asked similar questions. While we had to write some of the more unusual questions ourselves, we could borrow some language from other German-language surveys (like the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) or the German General Social Survey (ALLBUS)) for more common demographic questions. This will also give you an idea of what scales are commonly used for your topic. It is also important to ensure that every question provides a complete range of mutually exclusive answer options, although you may occasionally want to constrain the options available. For example, we considered adding an “I don’t know” option when asking people to consider whether someone had a migration background, but we instead decided to force them to choose between “yes” and “no” because this is more useful for our purposes.

Another important consideration is the order of the questions and answer options. This may seem tedious, but order can have serious implications for the results of your study. In our case, we chose to ask questions about respondents’ immigration attitudes before showing them the treatment because we were concerned that the treatment could actually change someone’s attitudes in the short term. On the other hand, asking a question like this at the beginning of a survey might prime participants to think about immigration, which might not be ideal if you were trying to conceal the true intent of your study. These kind of effects are called “order effects” in survey terminology, and it’s worth carefully considering how they might affect your project (Strack 1992). Overall, questionnaire design is an art and I cannot describe every step in detail here, so you should consult resources like the GESIS Survey Guidelines for more information as you write your own.

Sampling and Power

While you plan your research, you will also want to consider your target sample. Here, you not only need to decide on the population you hope to sample from, such as Germans without migration background (in our case), but also the sample size you need in order to make statistically sound claims. Calculating sample size may require you to balance many practical and theoretical considerations, as described in this recent paper (Lakens 2021). Some of these considerations might be how large of a sample you can afford to reach, effect sizes reported in previous research, and what the smallest substantively interesting effect size would be.

Ideally, you would determine your sample size with a power calculation, although these calculations can be complicated because of the many factors that influence power. Some calculations may require parameters like expected effect size that are difficult to estimate a priori, but pilot testing and previous research in your field can help you make an informed guess. I cannot cover all of the techniques you could use in such a short blog post, so you should explore previous work using similar designs and see how they have justified sample sizes for an idea of what methods might be most appropriate. When it comes to software, there are many options, fortunately including several that are free of charge. First, statistical software often includes built-in power commands, like “power” in Stata or “pwr” in R. Beyond these options, there are free programs that were created specifically for power calculations, like G*Power and Optimal Design.

There are also alternatives to traditional methods of power calculation, which can be especially useful for complex experimental designs. Because we were conducting a replication and had access to the original data source, we used a simulation-based technique. We duplicated Abascal’s data to make a large population from which we then drew many samples, assuming that the effect size she finds is the true effect. For a power of 0.8, treatment effects in 80% of these samples should be significant. (For more information on this approach, see Arnold et al. (2011).) A drawback of this method is that it required us to make assumptions about the effect size and variance based on U.S. data, which may not accurately predict responses in the German context.

Determining your target population, on the other hand, is mainly based on theoretical considerations. We pursued a sample that was representative of the adult German population without migration background in terms of gender, age, education, employment status, and region (East/West). To ensure balance on age and gender, we implemented quotas by gender and age, meaning that our sample would include a fixed number of men and women in each of three age groups. Note that your survey provider may be able to help you restrict your sample to certain demographic groups, but you may also need to implement screening questions to ensure the right sample composition. In our case, we had to screen for migration background and program quotas ourselves.

It is also important to note that despite our efforts to create a representative sample, samples drawn from online access panels may suffer from selection bias (Bethlehem 2010). Participants must have Internet access, find the provider’s website, and opt into taking the survey, and people who do this may differ from those who do not on variables both observed and unobserved. While some have proposed methods like propensity scores to correct for this bias (Schonlau et al. 2009), this should be considered a weakness of online access panels, especially when extrapolating results to the general population.

Ethical Approval

Once you have generally decided on your research design and your survey population, it is a good idea to start your application for ethical approval.

Based on our experience, the application itself is generally not too time-consuming unless your design brings up many ethical issues, but the approval process can take several weeks or even months depending on your institution. It has historically taken us about 4-6 weeks to get approval at the University of Mannheim. You should definitely plan ahead, because it is critical that you have this approval before beginning the data collection. This is not only to ensure that you are acting within the ethical and legal guidelines of your institution and your field of research, but also because many journals require ethical approval for any work they publish.

When do you need to apply for ethical approval? Your institution’s rules may vary, but the University of Mannheim requires it for any research on humans that:

- involves any personal or personally identifiable data

- deceives subjects

- involves psychological or physical health risks

- triggers strong emotions or asks about traumatic experiences

- manipulates subjects’ self-image

- involves minors, or

- presents risks to human dignity, life, health, and peaceful coexistence.

In our case, the first two bullets applied. Any demographic information about a respondent counts as personal data, even if it could not be used to identify any specific person, so your research will almost certainly collect some personal data. Additionally, we employed deception by withholding the purpose of the study from respondents until the end of the survey, which we had to address by debriefing all participants after the survey was completed. If you are unsure whether your study requires ethical approval or not, it is a good idea to ask the staff person associated with your institution’s ethics committee. You should also look at their website, which might have additional information to help you plan your application. (Researchers in Mannheim can find an application checklist and other information here.)

Your application should explain the ethical issues that will arise as part of conducting your research. You should explain why these features (like deception or data collection) are necessary for your design, and explain how you are minimizing any potential harms associated with them. You will also want to include as much information about your survey as you can, possibly including any planned debriefing text as well as the invitation to the survey, and maybe even the entire questionnaire depending on the expectations of your institution.

Another area that you may need to address in your application is data protection. This is perhaps especially important to researchers working in the European Union due to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) passed in 2016. I am not a lawyer and cannot provide a legal opinion on what regulations may apply to your research, but luckily the BERD @ NFDI in Mannheim has put together a useful tool called the Interactive Virtual Assistant that can give you more information on this topic (unfortunately only in German for now, but an English version is planned). In general, you should try to limit the amount of personal data you collect as much as possible, and make a plan to store this data securely. You will also want to avoid collecting any information that could be used to uniquely identify any of your respondents (or “personally identifiable information”, also called PII). Note that PII is not limited to names or addresses, but also includes combinations of variables that could identify a single person (such as a combination of ethnicity, age, and postal code). The ethics committee may be especially critical of designs that require the collection of such information.

Pre-Registration

Once you have received ethical approval and have firmly decided on your design, you should consider pre-registering your research. A pre-registration is simply a report of your hypotheses, data source, and planned research design that you write and upload to a repository before starting data collection. This is meant to prevent practices like selective reporting and p-hacking, and to disclose confirmatory and exploratory analyses, which makes your decision-making more transparent to those who read and evaluate your work (Nosek et al. 2018). This is certainly not a required step, but one that can help you plan and motivate your research, and that promotes principles of open science. One important thing to note is that pre-registering your design does not forbid you from performing exploratory analyses or even making design changes later on; it merely requires that you disclose that you have done so (Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn 2021).

If you would like to pre-register your study, you can find several useful templates on OSF. A pre-registration will only require you to briefly describe your hypotheses, design, and planned analysis, information that you may have already collected for your ethics application. Once you have filled out your template, you can upload your pre-registration to a repository like OSF or AsPredicted (among others), where it will be given a timestamp to verify when it was posted. Once posted, your pre-registration can be embargoed, making it invisible for several months while you complete your research. Note that you can also create an anonymized link to your pre-registration if you would like to include it in a manuscript submitted for peer review. If you are looking for an example, here is our pre-registration, although note that ours uses the “Replication Recipe” template designed specifically for replications.

Data Collection

Online Access Panels

You have planned your research, you received ethical approval, and you pre-registered your study – now you can finally begin collecting data. But we are still missing one key element: where is the data coming from? This is where an online access panel comes in. Online access panels have been used to study a variety of topics in the social sciences in recent years, from support for democracy to immigration attitudes, among many other examples. They have also been a popular method of studying reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic, as they are relatively cheap, quick to deploy, and do not require in-person contact. Despite these benefits, there are also drawbacks that you should be aware of before collecting data. I have listed some of the main pros and cons below.

Pros:

- Fast data collection

- Relatively low cost

- Possibility of accessing a representative (non-student) sample

- International data collection possible

Cons:

- Only include internet users

- Self-selection into participation can lead to biased population estimates (Bethlehem 2010)

- Some users may respond carelessly to get incentives

- Potential loss of naivete (but not as much as MTurk, see Chandler et al. (2019))

- May be difficult to achieve large sample of minority groups

If you decide that an online access panel might be a good fit for your research, your first step will be to compare prices and collect different offers.

Your institution will likely have rules about how many cost estimates you should collect (we needed three). You will want to contact several firms and provide them with information about your desired sample (especially size and any sample restrictions you want to impose), the timing you are hoping for, and the characteristics of your survey (programmed yourself or by the firm, mobile and/or web, time to complete). Make sure you request a large enough sample that you can run some pilot tests as well (more on this shortly). The providers you can choose from will depend on your desired population, but some of the larger firms in Germany include Bilendi/Respondi, Dynata, Kantar Public, and YouGov. However, this is not a complete list, so you might consider asking colleagues or looking through the literature to see what providers might be a good fit for your planned sample. Throughout this process, you should also be in contact with your institution’s procurement department to make sure you are following all institutional rules. In our case, two providers sent us quotes and a third declined to bid on the project as they could not meet the specifications we asked for (this however still counted as a quote at our institution).

Programming

One decision you will have to make while getting quotes from survey companies is whether you plan to program your survey yourself, or whether you would like the company to program it for you. While it is certainly easier to “leave it to the experts”, programming the survey yourself is cheaper and gives you more control over the process, especially when it comes to implementing features like randomization. If you would like to try programming yourself, you might start by asking your institution whether they have a license for survey software. One of the most commonly used tools is Qualtrics, which requires little to no programming knowledge for simple setups, but is generally not free (except for surveys with fewer than 100 respondents).

Other tools you may consider are oTree, which is free and open source, and well-suited for interactive experiments and behavioral games (although more complicated to program), or EFS Survey Unipark, a web-based service which is often available through German universities. No matter which software you choose, remember that the time and attention of your participants is valuable, and you should always strive to create an attractive and easy-to-use interface for your participants.

Pilot Testing and Data Collection

Depending on the complexity of your design, you may also want to consider running some pilot tests before your main data collection to ensure that your survey works as intended. As one example, you might use a pilot test to identify any potential order effects by testing two versions of the survey where the questions are presented in a different order. In the case of our survey, we wanted to check a couple of things: first, that the treatment had an effect on ratings, and second, that the photos were perceived as expected (i.e. native German, migration background, or ambiguous). In our first pilot test, we found that many of our respondents did not understand the treatment, and that we needed to include more ambiguous photos. We then ran a second pilot test where we added a text description to the treatment graphs and required respondents to stay on the treatment page for one minute, which significantly improved respondents’ comprehension. Based on this experience, I would recommend that you plan for more pilot testing than you think you will need.

After our pilot tests, we started our data collection. It only took us about one week to collect just over 1,100 responses, although your experience may vary depending on the specific population you are sampling. Targeting smaller groups or older populations may take longer. Once we closed data collection, we also carefully cleaned the data. One drawback of online access panels is that some participants may speed through the survey in order to earn incentives. Some telltale signs of this are a very short completion time, “straightlining” responses (such as always choosing the first option), or nonsensical answers to open-ended questions. It is thus essential that you look through your data before analysis and screen out any cases that you think might be invalid. In our survey, we dropped 25 responses for a final sample size of 1,077.

Data and Code Sharing

Once you have collected your data and finished your analysis, it’s time to share your results with the world! Of course you will write up your results in a manuscript, but you should also consider sharing your data and code with other researchers. Like pre-registration, this is optional, and this may not be feasible if your analysis relies heavily on proprietary data, but data sharing is becoming increasingly common in social science research, and may even be requested by some journals. Sharing your data and code fosters transparency and reproducibility, but there are also more self-interested reasons to share: uploading your work can open new opportunities for collaboration and generate more citations for your work.

When you are preparing to share your data and code, it is important to ask yourself: could another researcher reproduce your results without any additional information? In your dataset, this means ensuring clear coding and labeling, perhaps in a separate codebook file. It also means compiling your questionnaires so that people can see the source of the data (and translating them, if necessary). Perhaps most importantly, make sure that you anonymize or delete any personally identifiable information – refer back to your ethics application and be sure that you are doing what you promised to do. If your analysis includes other data sources that you do not own, you should also make sure to exclude these from your dataset (while informing users about where they can be accessed, and providing code that allows users to merge external data to your own). You can find more information on data preparation from ICPSR and GESIS. In your code, make sure you include labels to describe what each section does and that you reference all required packages. You should also have multiple people test your code, ideally someone who was not involved in the project, to ensure that everything is clear and that it works (ideally across different systems) as intended.

Once your code and data are replication-ready, you can upload them to a repository of your choice. You want to choose a repository that can ensure long-term preservation and a persistent identifier (such as a URL or DOI) so that people can find your information. Also make sure that your data will be accessible to other researchers, and if needed that it can be accessed anonymously during the peer review process. Some commonly used (and free!) repositories in the social sciences include OSF, Harvard Dataverse, ICPSR, and GESIS’ SowiDataNet|datorium. You might also check with your university library, as some institutions may have their own repository (like Mannheim’s MADOC).

Conclusion

If you have made it through all of these steps, congratulations on finishing your first data collection! As you can see, a lot of planning goes into any survey experiment. Despite this, I think it is worth the trouble. Collecting your own data can be a creative, rewarding, and even fun process that allows you to explore entirely new scientific questions. I hope this post has encouraged you to try it out for yourself, and I wish you the best of luck with your research.

Further readings

- Mutz, D. C. (2011). Population-based survey experiments. Princeton University Press.

- Auspurg, K., & Hinz, T. (2014). Factorial survey experiments (Vol. 175). Sage Publications.

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2021). Conjoint Survey Experiments. In J. Druckman & D. Green (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Political Science (pp. 19-41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salganik, M. J. (2019). Bit by bit: Social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press.

- Callegaro, M., Baker, R. P., Bethlehem, J., Göritz, A. S., Krosnick, J. A. & Lavrakas, P. J. (2014). Online Panel Research: A Data Quality Perspective. Wiley.

About the presenter

Joshua Hellyer is a doctoral researcher at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES). His research focuses on discrimination against ethnic and sexual minorities, particularly in the housing and labor markets.

References

Abascal, Maria. 2020. “Contraction as a Response to Group Threat: Demographic Decline and Whites’ Classification of People Who Are Ambiguously White.” American Sociological Review 85 (2): 298–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420905127.

Arnold, Benjamin F., Daniel R. Hogan, John M. Colford, and Alan E. Hubbard. 2011. “Simulation Methods to Estimate Design Power: An Overview for Applied Research.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (1): 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-94.

Bethlehem, Jelke. 2010. “Selection Bias in Web Surveys.” International Statistical Review 78 (2): 161–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00112.x.

Chandler, Jesse, Cheskie Rosenzweig, Aaron J. Moss, Jonathan Robinson, and Leib Litman. 2019. “Online Panels in Social Science Research: Expanding Sampling Methods Beyond Mechanical Turk.” Behavior Research Methods 51 (5): 2022–38. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01273-7.

Gereke, Johanna, Joshua Hellyer, Jan Behnert, Saskia Exner, Alexander Herbel, Felix Jäger, Dean Lajic, et al. 2022. “Demographic Change and Group Boundaries in Germany: The Effect of Projected Demographic Decline on Perceptions of Who Has a Migration Background.” Sociological Science 9.

Lakens, Daniël. 2021. “Sample Size Justification.” PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9d3yf.

Nosek, Brian A., Charles R. Ebersole, Alexander C. DeHaven, and David T. Mellor. 2018. “The Preregistration Revolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (11): 2600–2606. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114.

Schonlau, Matthias, Arthur van Soest, Arie Kapteyn, and Mick Couper. 2009. “Selection Bias in Web Surveys and the Use of Propensity Scores.” Sociological Methods & Research 37 (3): 291–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108327128.

Simmons, Joseph P., Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn. 2021. “Pre-Registration: Why and How.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 31 (1): 151–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1208.

Strack, Fritz. 1992. “‘Order Effects’ in Survey Research: Activation and Information Functions of Preceding Questions.” In Context Effects in Social and Psychological Research, edited by Norbert Schwarz and Seymour Sudman, 23–34. New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-2848-6_3.